Margaux Plessy: “Drawing is a dance, one that leaves a trace.” With these words, Emmanuel Deschodt invites us into his world—a place where movement and emotion converge, transforming drawing into an act of liberation. Emmanuel, your creative process is strikingly physical and visceral. Can you tell us more about how this approach took shape and what it means to you?

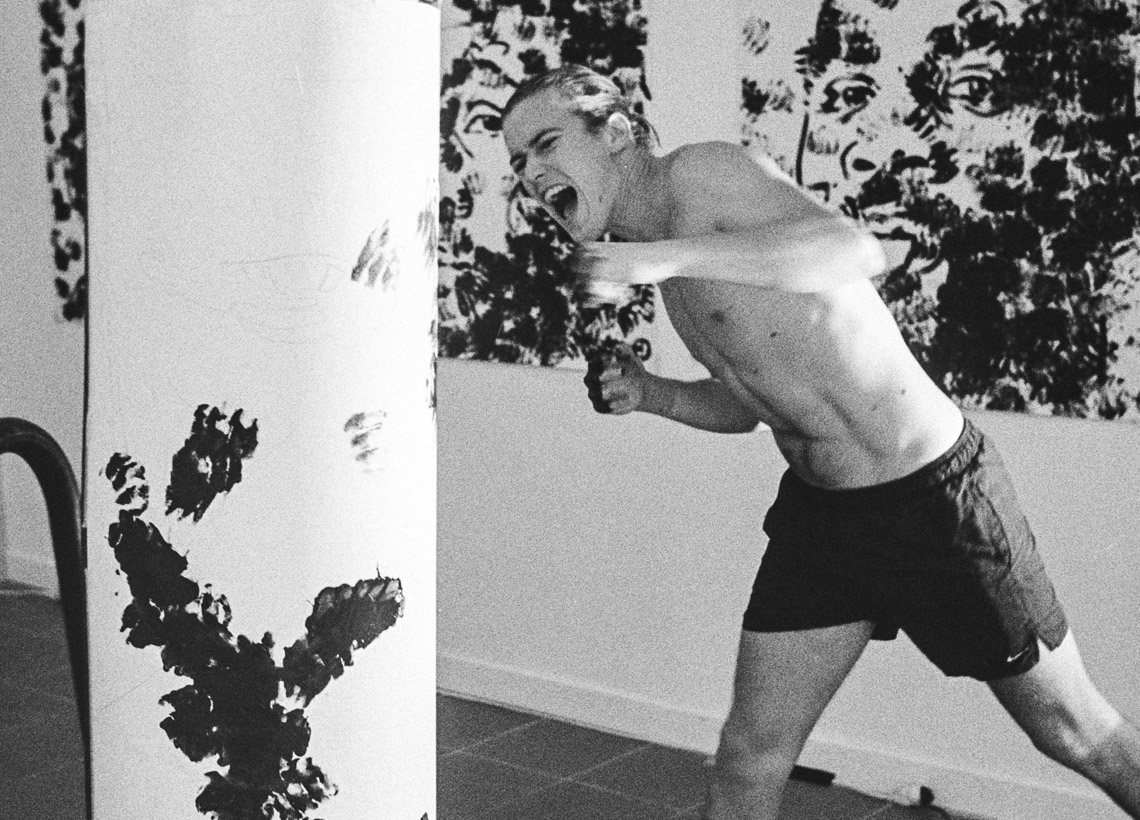

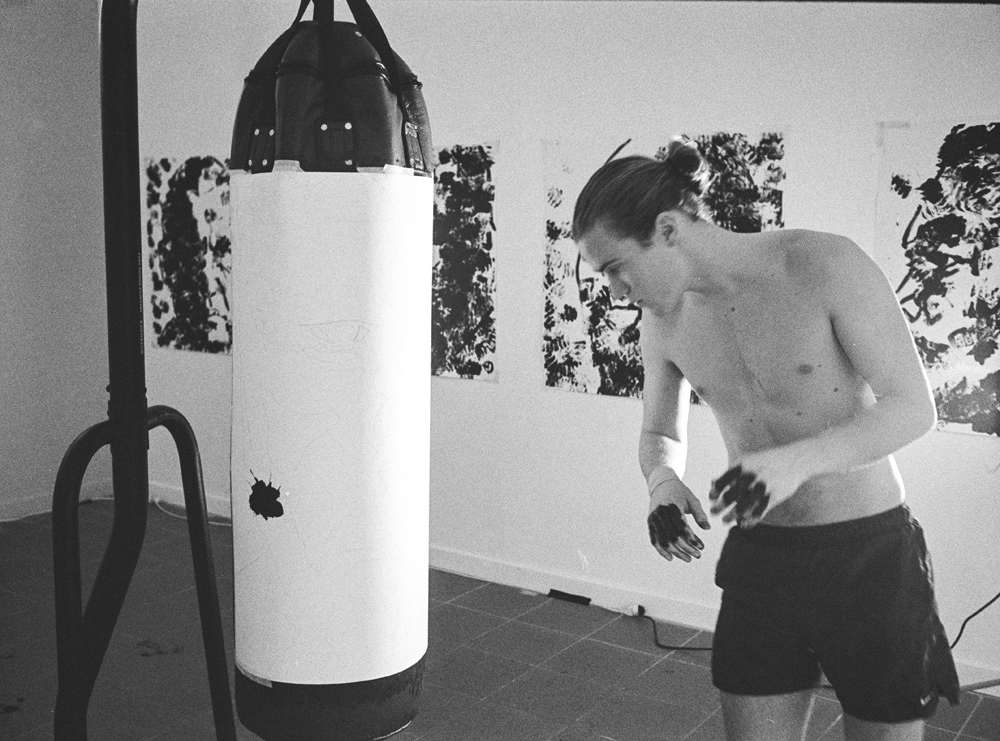

Emmanuel Deschodt: Drawings is a dance, one of those that leaves a trace. Often, it’s my hand, adorned with a pen or a brush, that swings above the paper. Sometimes, it’s my entire body that moves around my canvas stretched over a punching bag. The bristles of the brush no longer caress the fibers of the paper, they’re replaced by my fists, smeared with paint. This second dance, the most complete, the most immediate, the most brutal and definitive, allows me to leave the imprint of my impulses on the canvas and free myself.

Emmanuel, can you start by telling me about your journey, your passion for art, for boxing, and the moment these two parts of your life came together?

For both drawing and boxing, my passion began so early that I can’t recall a specific triggering moment. I’ve been drawing for as long as I can remember, while I could only start boxing in a club at 14. I began merging my two passions at the very beginning of my studies at the Arts Deco, in Paris. We had to submit a project with a strong visual impact. I decided to print the traces of my fists in black ink on the poster we were given. Two years later, I was hardly boxing anymore, and I missed it; I decided to return to it by developing the concept I had created in my first year, to rediscover the sensations of boxing through my creative work

The beauty of dance lies in the immediacy of movement but also in its uniqueness. No movement can ever be reproduced exactly the same way twice. When you paint while dancing, you freeze these stolen moments. What do you think of this idea?

To reach the state that allows me to enter my pictorial dance, I warm up both physically and mentally. All the images of training, locker rooms, the ring, the crowd, and the opponent come back to me, helping me reach the level of adrenaline, excitement, and fear needed to start dancing around the bag. It’s no coincidence that my canvas is square: the white square represents the shape of the ring, the space where boxers can methodically unleash their violence, their impulses, to defeat their opponent, just as I methodically paint a figurative portrait. This white square is the place where my creative, violent, and fleeting impulses crystallize, turning my portraits into outlets with human gazes.

You say your work allows you to escape a life that’s too mundane. Do you think our generation no longer accepts banality? Do you think it takes something spectacular to surprise or even move people? In that sense, what role does performance play in your work?

My need to escape a life that’s too mundane is a deeply personal one; I know people who thrive in lives far more ordinary than mine. My performance isn’t a way to deliver something spectacular to an audience. It’s quite the opposite: the audience allows me to regain the pressure I experienced during my small amateur career. It’s the gaze of others and the pressure it creates that enables me to more fully embody the boxer I strive to become through my performances. And thus, by adopting this role, I escape, even momentarily, my still-too-mundane life.

Between the struck paintings and the ink drawings, you transition from a sharp and definitive gesture to a soft and meticulous one. Do you think these two techniques complement each other? If so, how? How do your subjects differ between drawing and painting?

I developed and refined my performance out of a lack of adrenaline, a lack of movement. It was a time when I was barely boxing and was watching countless fights to draw and dissect the movements and dances of the boxers I admire. Those ink drawings allowed me to mentally immerse myself in the world of the sport, but the movement of my brush was so far removed from the gestures I was watching and representing that this drawing exercise eventually created a void. A lack of movement pushed me to rediscover impact as a creative gesture in my practice.

You seem to place particular importance on an imaginary, fantasized world, one that belongs only to you and that only you can access. Yet, your subjects are often very real. Is it this imaginary realm that allows you to create?

The fantasized world I speak of is deeply rooted in reality. It’s populated by real people, living or dead, and its scenery consists of real places or ones that once existed. The only fantasy of this world is that it doesn’t abide by the constraints of time, which allows me to meet people who are no longer alive. It’s a world deeply tinged with nostalgia and a spirit more romantic than the one of our era.

How does movement translate emotionally into your work?

Total movement, the movement of boxing, the movement of dance, is my way of letting action consume the emotions that limit or slow me down. By waltzing around the punching bag, by throwing my fists against the canvas, I rid myself of my fears, my hesitations. I free myself.

Image © Emmanuel Deschodt performing, image by Marc le Vaillant

Comments