Posted: February 5th, 2016 -

Category: Exhibitions, Voices

A CONVERSATION WITH BERNAR VENET – PART II: FROM MINIMALISM TO EQUATIONS

A lot of debate centered around modern and contemporary art has been based on the problem of meaning. Since the demise of representational art, philosophers and art critics have wrestled with the problem of finding meaning in the abstract. From Emmanuel Kant to Roland Barthes, Clement Greenberg to Jacques Derrida, different theories have been proposed on how to interpret a piece of modern art. Areas of study such as semiotics and iconography have focused on how to extract a message from what initially appears to be a random collection of shapes and colours.

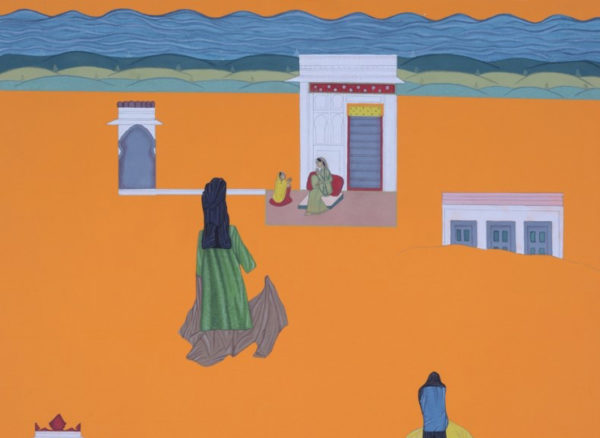

Bernar Venet, however, is determined to challenge the well-worn ideas and theories of art. In his talk at the National Library Building on September 24th, he described his visit to New York in 1966 where he visited the Whitney Museum and experienced a minimalist exhibition for the first time.

He was impressed with the work of artists such as Carl Andre and Richard Morris, who created pieces with no intuitive composition or meaning; in his own words, a ‘radical new way’ to create art.

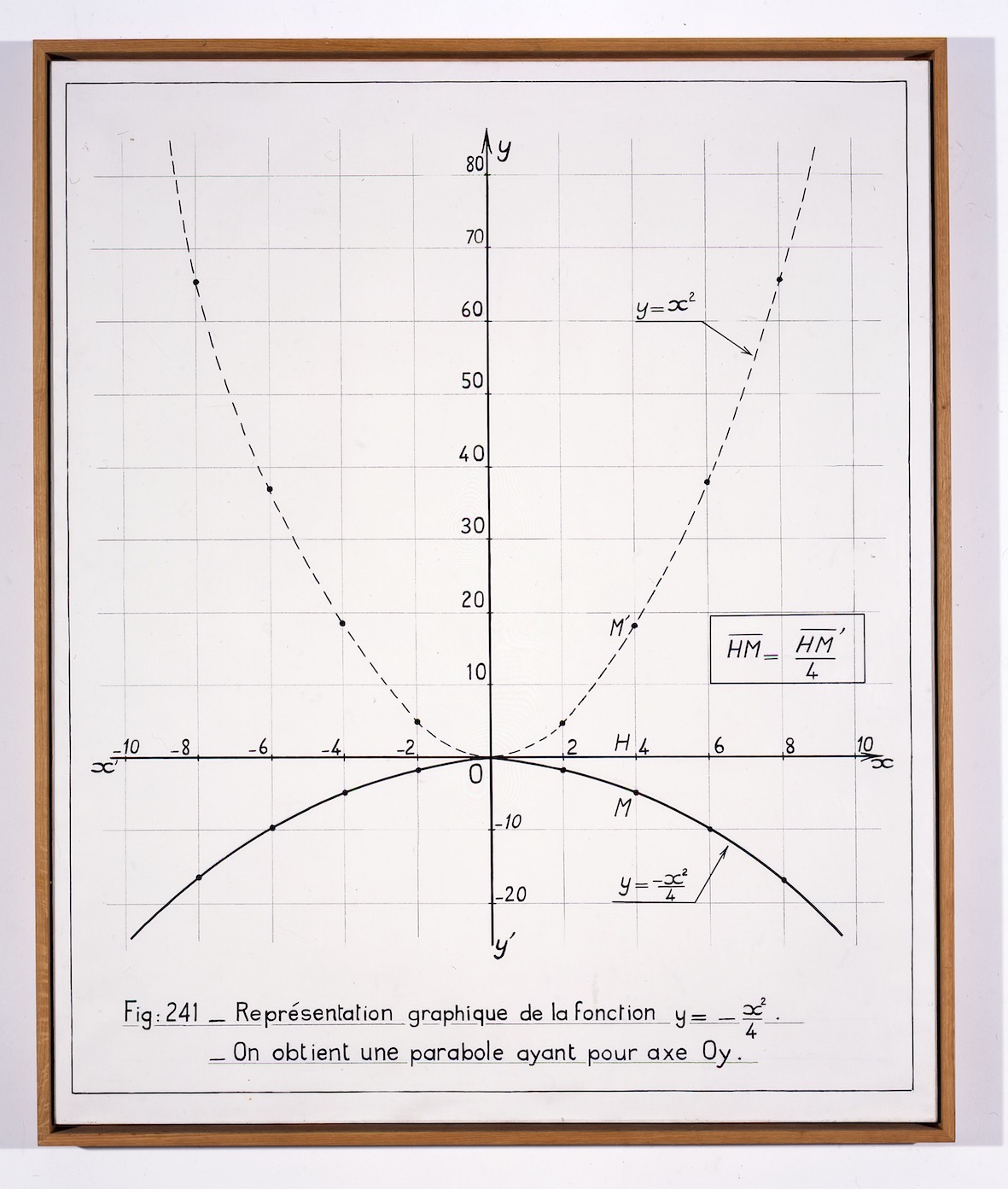

At around the same time, Venet was experimenting with presenting industrial products as sculpture. He created a series of tubes that year, but due to funding restrictions was limited to small pieces. Frustrated at not being able to created larger works, he looked at the architectural drawings used to design the sculptures he could not afford to create, and realised that he found the drawings themselves more visually interesting than the final object. He theorised that if he were to display just the drawing, then the viewer could visualise the work for themselves. He also liked the simplicity of presenting a diagram, as it purely factual; one cannot determine any kind of alternative meaning from a graph; there is no room for analysis of the artist or the artwork style, as it purely represents the object and its dimensions.

This led to a series of industrial drawings, which allowed him to develop the idea of exhibiting diagrams further. He began to shift towards a more radical theme of canvases that contained mathematical graphs and formulae.

During the talk, Venet recounted an incident when a friend visited his studio to see his first graph paintings, and declared ‘this is not art, this is mathematics.’ Venet passionately countered this by theorising that if art history had no tradition of portraiture, and one day an artist decided to paint a picture of his wife, perhaps someone would say ‘this is not art, this is your wife!’

Thus, Venet believes we are all conditioned by what we learn and by what we see in books about art, and that until an artist pushes the boundaries of what we call art, we think it can only be a set category of objects. In paintings mathematical graphs, he has created works that don’t look like either figurative or abstract paintings. They are also entirely rational and objective; one cannot seek emotion or alternative interpretation in them as they present pure information.

The theme of mathematics is something Venet would come back to later in his career. In another anecdote, he described a day when he was bored in his New York loft apartment, and decided to take down all the framed works hanging there in order to paint a huge mathematical equation directly onto the wall. By removing the idea of a frame, he hoped to continue pushing the boundary of what looks like art. Furthermore, the use of equations is something that has not previously been seen in the visual tradition of abstract art, which Vernet argues makes it ‘more abstract than abstract paintings’. In fact, abstract art is often seen as a way for an artist to express himself more easily than within representational art, as the lack of recognisable subject matter provokes viewers to seek meaning from the colours and shapes used instead.

It is no coincidence that many critical theories about the meaning of art were being written at around the same time as the rise of modern and abstract art. Venet, on the other hand, has sought to create a new category entirely by creating abstract pieces that are entirely devoid of interpretation.

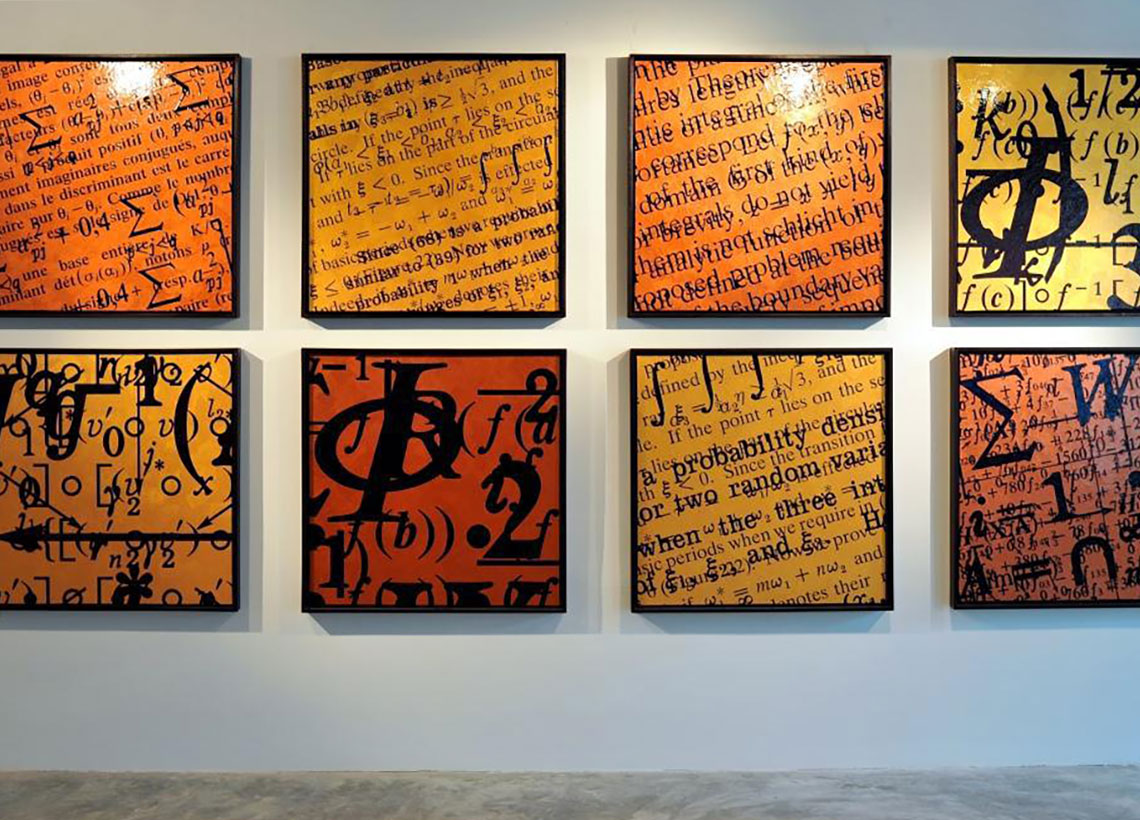

The continued theme of mathematics has provoked many people to ask Venet why he uses it, and if he has studied mathematics himself. However, at the NLB he explained that in fact the case is the opposite; he can only view his work as abstract if he doesn’t understand the equations. If he is able to understand and ‘read’ the text in his pieces, then it immediately stops looking like an abstract painting to him. He also confessed that he becomes quickly bored with things that he understands, which is why he has continued to play around with the mathematical theme, as it is something beyond his comprehension. To make sure this is the case with the viewer too, he then started layering equations on top of each other, rendering them unreadable.

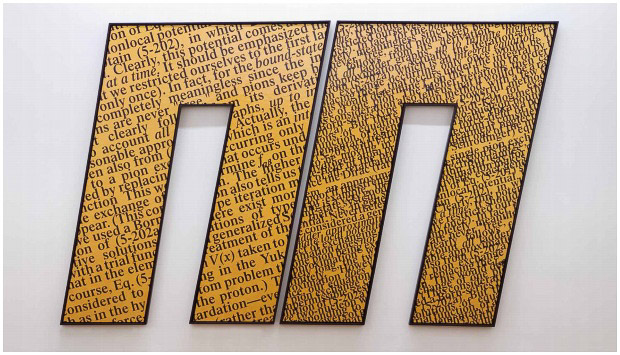

The recent series entitled ‘saturation paintings’ features mathematical motifs on shaped canvases. The shape of the frames also cuts off sections of equations and text, further abstracting them as they are then left incomplete and impossible for anyone to understand.

While Venet says he has ‘no rational explanation’ for the shift onto shaped canvases, he does believe that by playing with the shape and design of the frame, he is further questioning the visual traditions of art, and continuing his quest to make his art interesting.

Comments