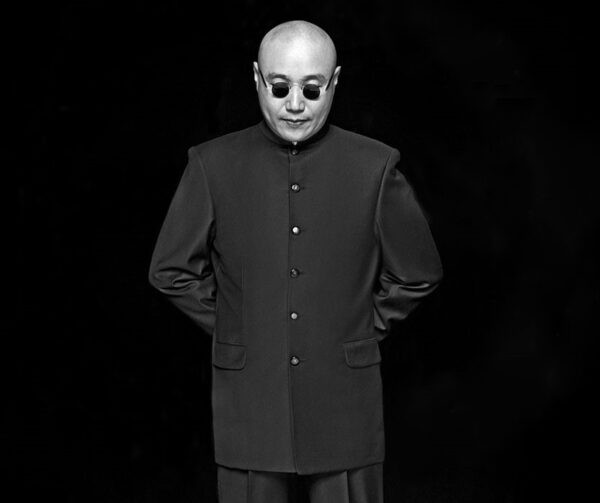

Dane Patterson is an American artist using photo-realistic details to depict meticulously staged disarray in his drawings. He takes inspiration from objects and begins his creating process by photographing models precariously and playfully covered in random objects. With his particular drawing method, Dane Patterson achieves photorealism with elaborate composition in which he engages the figures and the objects in an interdependent dialogue.

Can you tell us a bit more about your personal background and how you came to art?

My father is an artist, and for as long as I can remember I’ve been drawing. Growing up, I saw him make work, and I’ve always had access to art materials. When I was young I became really interested in drawing comics, and I think that a certain attraction to an off-kilter subject matter developed from that interest.

Your drawings are often featuring a black and white portrait or an indoor scene with a complex composition. Aesthetically they have a lot in common with photography.

What link are you trying to sew between drawing and photography?

I’m interested in the way that a photograph has the potential to provide the viewer with information about a specific moment in time. I’d like that quality in my drawings to whatever degree possible. I’d like for there to be no generality. The content is then about specific objects and specific people. There’s an energy to that differentiation. Photorealism is an entry point for the viewer in some ways. It’s familiar. I like that someone might say, oh, I have that shirt, or that mug. It brings them in, and hopefully the content or context can be considered with more familiarity.

What is your creative process? Do you arrange and photograph your models or scenes before drawing them?

I typically work in two stages. There is a starting stage where I play around with objects and materials and I work very much in a sculptural way. Ultimately, the end result of this practice is documented with a photograph. Sometimes the photograph works well and it becomes a finished work. More times than not though, I move from the photo to drawing with graphite to precisely render this source photo. I love drawing, and I feel that this stage of the work, because of its details, gets me much more acquainted with the content, and depending on the image, gives it a different energy, intensity, or obsessive quality.

Lately though I’ve made a point to do some works that abandon my usual process to a degree. Culling from a variety of photographic sources, whether magazines or the internet, I create an image that is in essence a photomontage rendered in graphite with as many details as I’m able to.

You use graphite on paper. Why are you particularly attracted to this medium?

I think I’ve focused on graphite as a medium because it provides the most control over the depiction of the content. I’m also interested in the slowness of working with a pencil. It promotes a state of concentration, like meditation in a way. I’m attracted to the paradox between the sometimes quick events depicted in the photo source and the labored process that is used to render them. One improvised photo session with a model might only take a few minutes to set up and photograph, but that can then take weeks to render accurately.

Your art seems to defy daily life, triviality and routine as it unveils important contrasts and disturbing elements. What is your view on this?

I think that there is a lot to point out, and to work against in daily life, particularly with respect to American culture. We are creatures of habit and we can quickly fall into routine. We’re rarely aware of the way we compartmentalize everything in our lives, or have had things defined and compartmentalized for us. With this in mind I like to present familiar objects and materials used outside of their typical function. It’s an absurdist gesture, with random combinations of materials and information turning specific cultural content on its head.

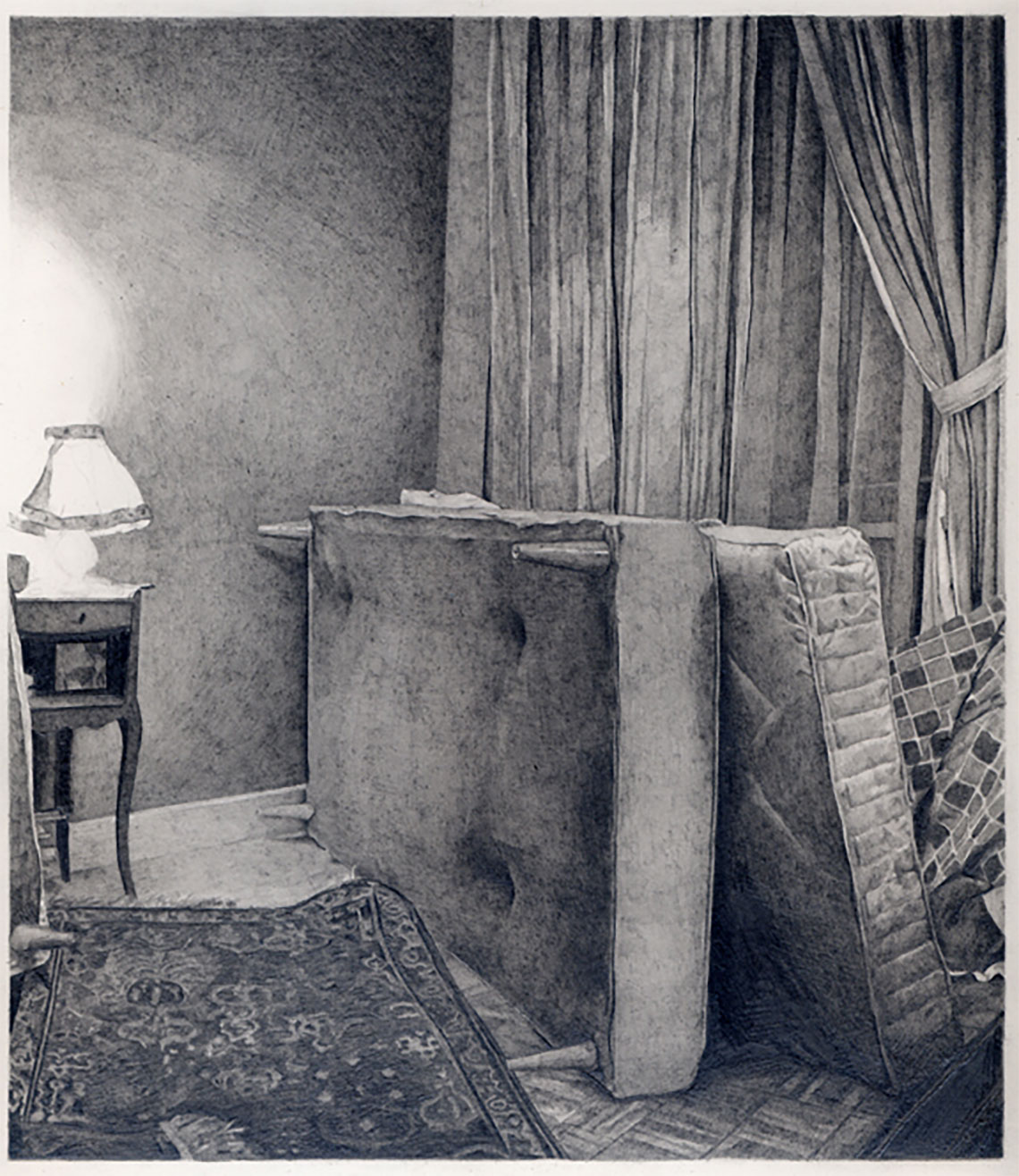

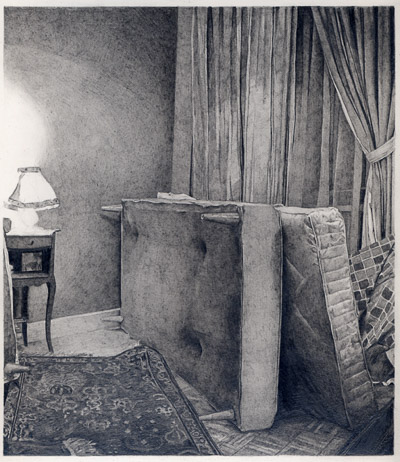

Your drawings are extremely detailed and seem to picture a very precise moment. For example the Dining Arrangement #2, looks like a crime scene with objects in disarray. Is your art depicting reality through instantaneity?

I think that the trope of photo representation does help me to achieve a sense of immediacy in the work. I think it’s important to address a very specific moment, an actual event or composed situation. The drawing Dining Arrangement #2 depicts a domestic scene at a moment in time when every object has been placed incorrectly. The “break in quality” is definitely there, and it tends to make the images seem like they happened quickly, in a panicked way. But it is actually a slow process of meticulous arrangement that creates the image, nothing is ever broken or ruined, but I like that it promotes a narrative that states otherwise.

It’s interesting to me that seeing familiar domestic objects, when positioned differently, can become disconcerting. The act of repositioning the familiar reads as an act of violence or at least the evidence of such. A toaster is designed to rest on a surface in a particular manner, and when placed on its side it reads to us as an error. This becomes disconcerting to see the entirety of a room presented this way.

In your portraits, you assign a panel of diverse objects to the characters. Is it a way to reach their identity through their relationships with objects?

I think that’s one reading, but for me it’s not so much about personal identity. I’m attracted to working with portraiture but at the same time I’m looking for ways to undermine it. The objects that I put on people began as a ridiculous gesture. There was comedy involved for me. As I’ve developed the body of work it’s evolved into an aesthetic consideration as well – an interest in a certain object when placed in contrast with another. I am working towards depicting something with sculptural consideration that in turn operates to negate the typical purpose of a portrait which is to display a particular person. For my purposes I enjoy using friends or people I know in my work, but for conceptual purposes the person could be anyone. I think in some ways a human in a portrait reflects the viewer and in turn brings them mentally into the situation depicted.

The titles of your artworks sometimes seem quite ironic as in Bedroom Arrangement that alludes to a tidy and organized room. What is the role played by titles in your work?

For a very long time I resisted titles completely. I felt like I was taking away from the viewers’ relationship with my work by using language to title it. I’ve gotten past that and I now like to use titles to point to irony or conceptual intentions in drawing a subject.

You also work with other media such as video and sound. Can you tell us more about this practice and how it is linked to drawing?

Regarding video, I turn to it rather rarely. I think that I came to it as a way of exploring conceptual content that needed more narrative development. Physical actions and sounds can deliver an idea in totally different ways than a still image. I think I turn to other media when I feel that I’m not able to fully develop a concept in still images. When I work with sound I typically still think visually. I cut audio into fragments and arrange in the same way that I think about photo collage.

Comments