Posted: February 1st, 2016 -

Category: Voices

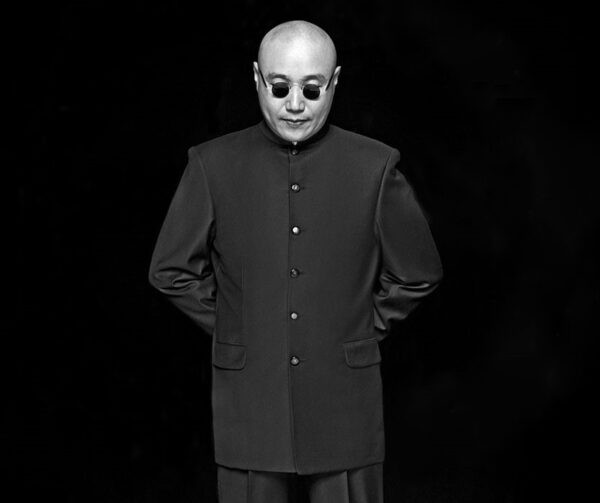

A CONVERSATION WITH BERNAR VENET – PART I: FROM TAR TO CHARCOAL

What makes a great artist?

Some might say technical skill, or the ability to create a piece of art that is aesthetically pleasing. Bernar Venet, however, began his talk at the National Library Building by stating that great artists ‘raise questions about the nature of art.’ In discussing his oeuvre, Venet attempted to demonstrate to his audience that he is not just a painter or a sculptor, but a ‘true artist’, because he has created works that have revolutionised the definition of art.

Apparently achieving such enlightenment at the tender age of eleven, Venet throughout his career has understood that an artist must continually question what he is doing in order to push the boundaries of art. With a reference to the French nineteenth century painter Gustave Courbet, who believed during his time that art history had already come to an end because all subject matters had been exhausted, Venet highlighted the importance of continual discovery and the invention of new concepts in art. This served as a nice introductory context for Venet to then provide a chronological in-depth description of his works, and how his ideas have progressed through the years.

One of the most interesting elements of the talk was the way in which he described the shifts from one style to another. The audience were treated to an insight into Venet’s continuing thought process, which was not only fascinating, but also drew attention to how seemingly tiny and random occurrences can create such a huge impact on an artist. The first example of this was during Venet’s army years, when at the age of 19 he happened to walk past a cliff where a huge load of tar had spilt and run down. In his own words, he was ‘very touched by the tar texture, black and oily, and the fact that gravity was creating the shape.’ This, combined with his love of the colour black, led him to start making paintings with tar, which were created very spontaneously and without composition to echo the markings of the tar spill on the cliff.

The making of these tar paintings led to the second example of how a random incident influenced Venet’s work; the tar in the studio apparently smelled very bad, so whilst walking around outside to escape the smell, he discovered a big pile of gravel mixed with tar. The heap inspired him to realise that he could go beyond two-dimensional works with tar, and instead shift towards sculptural works. However, the reality of the tar and gravel was that it was enormously heavy, so he opted to use charcoal as a replacement medium due to its similarity in colour and texture. The resulting pile became one of his most famous early works as well as one of the most experimental.

Venet was determined to shift away from sculptural tradition and create new parameters of what a sculpture could be. The horizontal nature of the pile is a direct opposition to the usual vertical nature of sculpture, in which the figure or object is usually standing upright. One might almost consider it closer to the reclining buddhas of East Asian tradition. In a continuation from his tar paintings, Venet is keen to realise the effects of gravity on the shaping of the sculpture.

Furthermore, in his pushing of sculptural boundaries, Venet decided to challenge the fetishist nature of traditional sculpture, and question the notion of the ‘original’ artwork. A pile of charcoal can never be exhibited the same way twice due to its random nature, meaning that it will always look different despite being the same piece. The charcoal itself is a medium that can be acquired anywhere; and Venet specifically did not want each realisation of his piece to be made of the same exact pieces of charcoal. This way, not only can the charcoal be returned to its original vendor once used, but the sculpture can be exhibited in more than one place at the same time. Yet each version is always ‘real’.

Comments