Art historian Michael Peppiatt, occasionally relates an anecdote of his time at Cambridge, studying art history in the 1960s. Briefly summarised, the curriculum didn’t think much of anything after the Renaissance, viewing everything since as a long, slow decline from that glorious golden age, a gradual process which only accelerated with the arrival of modern art. Understandably enough, Peppiatt rebelled against this dogma, diving head first into the English art scene of the time, a crucial early step in a storied career that would see him become a friend and chronicler of some of the leading lights of the age.

It almost goes without saying that the tendency to conceive of golden ages (and lament what comes after) is hardly an isolated phenomenon. For instance, Giorgio Vasari, artist and famed historian of the 16th century, described the Renaissance as a clean break from barbarous gothic traditions that had come before, hearkening instead to the golden age of the Classical era. In our own time, we might consider the Stuckists, who bemoan the existence of conceptual art as they yearn for figurative painting’s return to prominence. Regardless of period, it seems inevitable for some to declare the art of their time to be little more than a degenerate descendant of some point in the past.

Comparisons of this sort, however, rely on a relatively linear sense of how art changes through time, as well as a relatively stable conception of art as a whole. As Peppiatt related: Voices of Contemporary Art, our art-world traces its line of descent from a deeply European-centric (and later American as well) point of view – a habit of thought which persisted through much of the 20th century, even as artists’ adoption and assimilation of influences from the rest of the world accelerated.

In these early years of the 21st century, Peppiatt notes that this absolute dominion is, for all intents and purposes, a thing of the very recent past. Whereas fine art would once be traced in a single line of descent all the way back to the cave paintings of Lascaux, artists now emerge from every corner of the globe, bringing with them new histories and traditions; the centre of the art market, once firmly sited in Western Europe and the United States, is pulled east, though perhaps one day it will be hard to describe it as having a single centre.

Taken together, these tendencies within the globalisation of art – which Peppiatt refers to as the emergence of ‘world art’ – may form, if not an outright antidote, then at least a strong defense against the pervasive habit of wistfully imagining a lost-past golden age of art; such a profusion of traditions, origins, and chains of influence turn what was once a vaguely linear stem into a dense, tangled thicket, in which it makes even less sense to declare a single point to have been the incomparable apogee of art.

However, critics of the globalisation of art contend that the overall effect we may expect is one of homogenisation – both in terms of the passing fashions of the global art market, as well as globalisation’s perceived tendency to reduce the importance of place, and run roughshod over existing cultures.

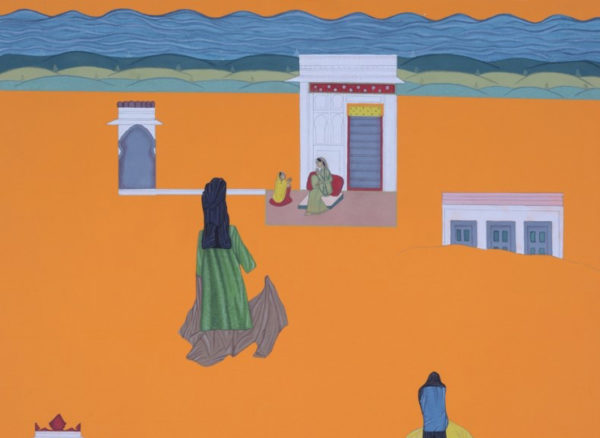

In response, Peppiatt notes that good artists will always find ways and means to negotiate with the pressures of market forces and passing trends; certainly not submitting in whole, not necessarily rejecting them outright, but, as artists have always done, filtering, interpreting, and adapting it to their own advantage. This tendency extends also to the sheer extent of inter-cultural communication now possible, with Peppiatt noting that it’s hardly a new phenomenon; artists borrow from each other constantly, just as the Romans borrowed from the Greeks, and the French Impressionists borrowed from Japanese ukiyo-e.

This sense of agile changeability and assimilation can be seen in the work of Doug and Mike Starn, which concerns itself with chaos, interconnectedness, and endless flux – a focus which extends to their methods of work, in which disparate disciplines and fields, such as architecture, photography, and performance, are interwoven as a matter of course. Their Big Bambú: You Can’t, You Don’t, and You Won’t Stop series of installations, for example, take the form of a sort of performative architecture – towering bamboo structures through which visitors may walk, constantly being assembled and disassembled across several months. Though the general spirit of the work seems to take a leaf from some blend of eastern spirituality and ecological sensitivity, the work’s title comes courtesy of American popular culture, via hippie comedians Cheech and Chong, as well as the punk-turned-hip-hop band, the Beastie Boys.

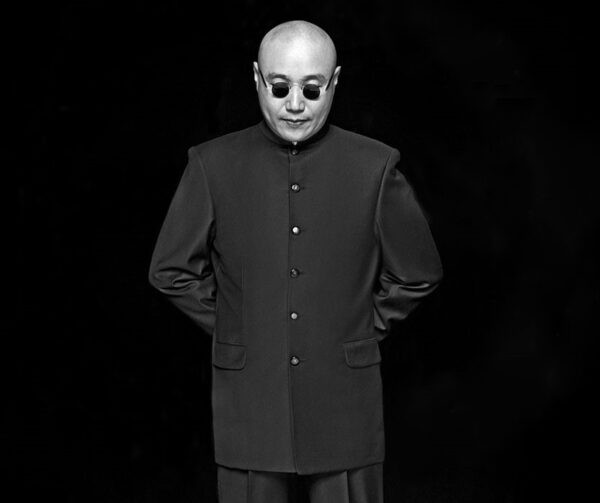

Bridging a greater gulf, at least in chronological terms, are the hieratic sculptures of Yves Dana, which owe a much to the time-worn forms and textures of ancient statuary and architecture in Egypt, the land of his birth. In keeping with the theme of remixing origins, traditions, and influences, however,

Dana would later be educated and practice in Switzerland; consequently, his sculptures, as one might surmise, are no pale reflection of Pharaonic monuments. Instead, his austere forms meld both the ancient and contemporary – evocative of both, but never fully one or the other.

Comments